|

|

|

|

The Christmas, Present. by J. Grey and R. Cane

In what could only be fairly described as the very homeliest of stony

hearths, a fire was crackling warmly, warding off the crisp winter evening

chill, and the cold air that prickled dryly at their skin, and nipped at their

chests as they breathed it deeply. The fire flickered away softly, spitting

embers into the air, as the people around it warmed the cold from their tired

limbs, and shared their good humour in generous measure.

In what could only be fairly described as the very homeliest of stony

hearths, a fire was crackling warmly, warding off the crisp winter evening

chill, and the cold air that prickled dryly at their skin, and nipped at their

chests as they breathed it deeply. The fire flickered away softly, spitting

embers into the air, as the people around it warmed the cold from their tired

limbs, and shared their good humour in generous measure.

For it had been a long day for them indeed, a day of winter nipping at their toes, of being chilled through to their very bones, and it had left them with ruddy reddened cheeks and beaming smiles.

Winter was at its height and it was the night before Christmas, a night of anticipation, of dreaming about the festivity that must so surely follow a good night of sleep. But sleep was not foremost on anyone's mind, the morrow promising so much kept notions of bed far from their thoughts.

Two children nuzzled close, pushing one another playfully as they sidled up to bask in the orange glowing embers of the fireplace.

Behind them, a man settled into a comfortable looking chair, smiling jovially as he sunk his haunches into its easy cushions, and it softly sighed as the wooden frame settled beneath his generous proportions. It was a scene of a welcoming home, a place of family and joy, of healthy appetites, and all the excesses of the season so far and of those still yet to come.

"Merry Christmas!" his friend gestured, with a raised glass of blood-red port.

"And to you." he said, raising his own glass in earnest reply.

The children played with a wooden top, watching it spin, singing to itself as it skipped and whirred across the smooth stone ledge of the fireplace. They giggled in excited awe as the plaything flashed its bright-coloured paint at them, spinning, spinning on, as if powered by some unseen hand and fated never to stop.

"And what a year this has truly been for us." Mr. Stanley sighed to himself, watching the gaiety of the excited children, and drawing a certain pleasure from being witness to such simple and innocent delight.

"Indeed." his friend agreed, for how could he not, amidst such a scene as this. "Thank you for inviting me to your home. You've made me feel most welcome, as always."

"You are welcome." He sipped at the fine port, and it was fine indeed; the best he had tried in many a long day. He had been saving this bottle for just such an occasion and it was quite clear he saw this visit as special indeed.

"And it's appreciated, as always." he told this closest of companions with earnest assurance.

Mr. Stanley shone a satisfied smile, as his attention flitted between the childish giggling, and the warm words of his oldest friend. "Well then, maybe you can do something for us?" He smiled knowingly, an infectious smile that wryly covered an innocent little secret.

His friend's face brightened in return, and he began to nod along. "Aye. Maybe I can, at that." He reached into his satchel and took from it a great bundle of worn papers, handling them with the largest measure of care, as if they were of some notable value indeed. For him, of course, there was nothing of any more notable value in all the land.

"Children," called Mr. Stanley.

They turned to face him, their toy forgotten in an instant.

"Your Uncle has something for us!" And something he truly had. He had a thing to share; a thing that needed to be shared; a thing demanding to be brought to the minds of others. And what was this thing? The children looked on with perplexed expressions of great expectations, and their guest seemed confident of meeting them at the very least.

"But Christmas is tomorrow." said the young girl, confused and curious, her voice almost a song as she slid up to the men's feet; her smaller brother nudging her to get out of his way, for still better a look at what rare treat had been prepared for them.

"Then this is a special gift indeed." he replied, passing a knowing wink to them both.

The other gentleman chimed in. "A special gift indeed, for this most special time. Tonight, is Christmas Eve; it's a night of tales to be told."

The children stared in rapt attention, and their attention was most undeniably his.

"Tonight is a night when strange things could happen both now, in the past, and in the unknown realm of tomorrow. Perhaps the far future, somewhere further than our imaginations can carry us."

As the children sat, waiting with bated breath, he set the scene with a flourish of his eyebrows, a wave of his wrist, and a lowering of his voice as he leant in towards them. The whole room his own, a canvas upon which he could paint their minds, from the brilliant palate of his imagination.

"And do I have a tale for you." he said, almost a whisper, serving only to raise their excitement. "I have a tale of things beyond your wildest imaginings. I have a tale that will make the very hair on your neck stand up to attention."

And they believed him, as well they should, for a tale was coming the likes they had never heard before. A tale that would take them to a place never before dreamed of, a time beyond the span of their years where things had changed beyond all comprehension. He would spin a tale that would leave them with a fresh new wonder for the world around them, so he believed. But he was a man who believed in the best of people, even though such a thing was rarely seen, in all honesty, and his hope for their imaginations may be a flight of fancy of his own. But still he believed in people, and wouldn't let his belief wane, even if his tale were to be told in a bleak house instead of one so bright and cheery. Such was the battle of life.

"A new story, then?" asked his close companion.

"Oh yes." he assured him with a solemn nod. "This is a new story indeed, and you, my dear friends, are the very first to hear of it."

"Really?" the young man enthused, with earnest pleasure, clapping his hands in childish glee. His children shared his bright enthusiasm, as they settled down to listen.

"I've saved it especially for you." he said with a nod, and passed a knowing wink to his friend.

"Well, don't keep us in suspense any longer!" said Mr. Stanley, in the best of humour.

"Yes indeed." he agreed. "Yes indeed. Is everybody ready then?"

They were, and they all nodded to attest this very fact.

"Very well." he began. "This story takes us far, far into tomorrow; another time; another place. And from there, our tale begins."

And begin it did.

![]()

The day was December 24th, Christmas Eve, and the hour was growing decidedly

late. Still, there was work to be done, and done the work must be. Mr. Ignorous

Crowe was a man who worked; he liked work, he liked to work, and he liked to

enjoy the things his work had brought him. In equal measure, he liked to enjoy

such things that the efforts of others had brought him also; and those, in fact,

had brought him very much more. He was also a man with an ageing and withered

body, and a heart in a far worse state of repair. He was motivated by the

trivial wants of that very heart, a heart that no longer had a sense of anything

but its own desires.

The day was December 24th, Christmas Eve, and the hour was growing decidedly

late. Still, there was work to be done, and done the work must be. Mr. Ignorous

Crowe was a man who worked; he liked work, he liked to work, and he liked to

enjoy the things his work had brought him. In equal measure, he liked to enjoy

such things that the efforts of others had brought him also; and those, in fact,

had brought him very much more. He was also a man with an ageing and withered

body, and a heart in a far worse state of repair. He was motivated by the

trivial wants of that very heart, a heart that no longer had a sense of anything

but its own desires.

He rose from his chair with a sigh, and a huff of solemn indignation. The time was ticking by, and the time for languishing in his office was long since past. It was time to the minute that he departed for the comforts of his home.

His office was luxurious by the standards aboard the station, and his business was considered to be of great import, perhaps more so by him than by anyone else, but there was nobody that could argue that his work held no benefit. You see, he had contracts with the Federation, the largest government since such things had been recorded, in all of living history; a most mighty coming together of peoples and creatures of every shape, colour and culture, united by a single purpose and a higher purpose too. No more were the only certainties of life to be death and taxes, for the economic happen-stance of this time meant that taxation was now merely a note in the history books. Death, however, remained a certainty, but we'd learned at the very least that we were under no obligation to pay for it. The simple fact of such contracts with such an agency as The Federation was, above all others, that it conferred him privileges that he continued to relish and enjoy, a step up from the more common of men.

"Mr. Hackerty!" he called out, shouting through the open doorway, his voice a growl of no faint menace.

The young man scrambled to his feet, nervously craning his neck, to see from which direction the voice that was yelling for him was coming from on this particular occasion. Mr. Hackerty was no stranger to being a recipient of the occasional yell. He was fairly well versed in receiving admonishment of all kinds, in fact, and absorbing insults and accusations were a particular speciality of his.

"Mr. Hackerty!" he called out again, shaking his head in silent rebuke, and jabbing his bony fists into his hips, as the toes of his right foot rhythmically tapped at the ground beneath. "Do you know the time, Mr. Hackerty? Do such things even concern such a simple man as yourself, or are you content to take up residence here, in this place of science and commerce, instead of your own assuredly humble domicile?"

"I surely do!" he called back, in the thick accent of a common man; an accent that was like fingernails scraped across a blackboard to the sensibilities of the mature and cynical old man, who considered himself to have more than a modicum of taste in such matters. Crowe cringed openly at the heavy London lilt that peppered his most humble words. "Why, it's late, Mr. Crowe, and my family are waiting for me."

Tom Hackerty was a small man, tubby, and weak in stature, but had an earnest smile almost permanently upon his face, and a demeanour to match. But all that had slipped away now, to be replaced with a frustrated disquiet.

"Late, indeed." repeated Crowe, with a sarcastic rolling of the eyes. "Late is hardly the time, now, is it? I wonder, could a man of your wits even care to put a number to that lateness? Could you cast a numerical figure with which to measure your guess to a more accurate degree?"

"Oh yes, sir." He lowered his gaze away from his employer's admonishing stare, the stare that dripped with the assumption of superiority; the glare that looked down through his nose at him, with little more than contempt. A look, indeed that belonged to a man who, in his mind, stood head and shoulders above his employee in terms of social stature. It troubled Mr. Crowe to no significantly large degree that without a single friend to speak of, his social stature was actually quite diminutive indeed. "Why, the bell chimes again, each time once more than last, with each new hour that hereby comes to pass. And besides, my astronomic petastropic pocket time piece is accurate to the smigden."

"Accurate to the smidgen?! Humbug!" he said sarcastically, with a yet more mocking note. "Well, with your smidgen accurate foreknowledge of the lateness of our Federation contract, I find myself wondering why you are not more motivated to fulfil your obligations?" He hissed his chagrin and narrowed his eyes in growing derision. "Your obligations to this company do not extend far beyond completing your work in the time allotted, and yet such a trivial task continues to elude you, straining your meagre abilities beyond their still more meagre limits. It's a sad fact that you're not as accurate-to-the-smidgen as your astrologic petascopic pocket watch, but considering the amount of currency you inevitably exchanged for such an item it's not unlikely that you are."

"But... it's Christmas, Sir." he said, shrugging in meek protest, his voice rising in the manner of suggesting that this was a question.

Such a thing meant nothing to Mr. Crowe, of course. Christmas was just another day, a mark on a calendar, and of no significance besides. That his employee felt differently about this matter was no concern of his, and why should it be so? To his mind, his responsibility stretched only so far as satisfying his own wants, just as other men were perfectly capable of satisfying their own in their turn. It never would occur to him to try to help his fellow men, but then, none of his fellow men had ever seen fit to help him in return. It was the way of things, and he saw no good reason for it to change, and nor would he change it, if ever such a reason were to present itself. He had resolved long ago that this was the way he was, and if the opinions of others were against him, then they would just have to learn to live with it. If anyone was indeed living with it, then they'd made no great attempt to communicate such concerns to his person. Nobody no longer living with them had communicated their concerns besides, but, of course anything was possible in a time so far removed from what we now know of as fact.

"Mr. Hackerty, the device should have been tested and ready this very morning, at the latest. I ask for results, yet all you deliver me are excuses. I'm rather fatigued with your excuses for not doing the job you agreed to do. You should take yourself to the Old Curiosity Shop and sell them a weekly bag of your nonsense; I'd wager you'd earn a lot more that way than you could from bartering your plodding talents in the workplace. "

And indeed, results had been few and far between, what he was saying was quite true in that sense, if not every sense. He scowled at the little engineer in something close to disgust, deservedly or otherwise. He remained silent for a moment, his gnarled hand resting upon the cool white metallic frame of his office door. The laboratory beyond was quiet, save for the hum of some great electrical mind upon which glimmered an occasional lamp, blinking on and off in warning, and the odd fluttering as cool air breezed through the room by some synthetic means far beyond our current learning.

"Sir, yesterday's deliveries arrived late. The scans we ordered were delayed, cos of the holidays; everything else has closed down. The work schedule didn't allow for..."

"The work schedule?! The schedule that you, yourself are in charge of managing? I'm most sorry, but if you lacked the foresight to anticipate such inevitabilities, then you only have yourself to blame; or perhaps blame should pass to your superior, for expecting too much of a simple little creature as yourself."

"But sir! You only put me in charge of work scheduling this very afternoon, after you fired Mr. Clusterbuckle, on the grounds of 'incompetency in the field of work scheduling'!"

"Don't you dare talk back to me young man!" he roared, bounding forward towards him, and wagging an accusing finger with unbridled fury. How many times had it been, now, that his junior employee had blamed his shortcomings on everything other than himself? He was moved to anger, his temples tightening, his face flushing, his heart pounding impotently in his wheezing old chest and he coughed and spluttered, near choking on his rage.

Mr. Hackerty stepped away in deference, shutting his eyes and gritting his teeth. "Sorry sir..."

Crowe allowed himself a smug smile. An ugly little smile to be sure; a smile of cruelty, and viciousness, and moreover, a smile of arrogant superiority. A smile quite unbefitting a man in a position of such respect, or a least of such respect as he imagined he commanded, but frequently a man's imagination was of little bearing on the nature of the world around him.

"This just isn't good enough, you know?" he huffed breathlessly, his ageing, tired bones feeling every moment of their years, and making sure he felt it right along with them. "If I wanted excuses, I surely wouldn't be employing the likes of you to make them for me; I would have you invent an electronic excuse making machine, and do away with the more troublesome aspects of employing an incompetent oath such as you are."

"I'm trying, Sir. I surely am!" Hackerty shrugged an empty apology, his eyes peering down to his cluttered desk, strewn as it was with tiny scientific objects, devices and gizmos, each wondrous thing holding value beyond measure in our time.

But Crowe's smile turned crueller still, before melting into a snarl. "See to it that you try harder then. I'm of half a mind to dock this from your wages; and the other half couldn't agree more."

Mr. Hackerty nodded his defeat; the empty promise of a halfwit. Could such a dullard truly grasp what was at stake; could he truly comprehend such a notion as value? Perhaps a common man lacked facility to accommodate such lofty goals, as resided in Mr Crowe's own ambition.

"Let me ask you a question, Mr. Hackerty. How much did your clothes cost you?" His eyes rolled up and down his employee's tasteless attire, sneering to himself; and why not indeed? His clothing was basic; it lacked flair, and it was cheap, the cheapest it could possibly be. It made his point admirably without another word needing to be spoken.

"Sir?" He looked down over them himself, lost as to the implied meaning all this might carry, but he must have known that such meaning would come at his own expense. "They cost nothing, sir. They're replicated."

And so they were, borne from reclaimed matter, solid reality broken down and shaped to the whims of man, by the fires of the most brilliant of sciences. In this world, replicated things were free, and carried no value of their own, for they could be had without compensation.

"Mine were woven right here on the station, by an accomplished tailor of considerable flair." Crowe ran his fingers along the silk-smooth grey fabric, the almost invisible seam beneath his wrinkled skin. "They are of the highest quality; they are beautiful to behold; they are comfortable. They tell a man who I am. One thing they are not, is cheap. Why, the material alone cost upwards of twelve hundred wing wangs. Do you understand me, Mr. Hackerty?"

He nodded meekly with a feeble little sigh.

"And this is who you are. You wrap yourself in valueless rags for all the world to look upon. You are happy to have nothing, and content to aspire to achieve nothing. Without dreams to climb to, you're nothing but a rung at the very bottom of a ladder; a ladder I'm climbing to the very top."

His employee winced at this harsh appraisal, and Crowe knew there could be no retort against it. He had made his point admirably, and there was nothing left to add. "Christmas means nothing to me, Mr. Hackerty." he said, with a fair degree of certainty. A degree of absolute certainty, if it must be said, and hardly a fair one, at that.

"But... my family, Sir." he grumbled, kicking an imagined ball of dust around the floor. Drawling through his heavy accent, he continued, "I just want to get back and be with them, tonight of all nights, good Sir."

"And you shall." He shook his head in dismay, at the narrowness of the man's vision, but he knew to expect no less. He was an employee, not a leader, and was doomed to be nothing more for all the days his lungs drew air.

"Really?" he said, a light kindled in his hopeful face.

"But of course!" he replied. He could see the excitement in his employee's eyes, and was soon to stamp down hard on such a fancy. "However, it seems to me you've got some work to catch up on first. I want the prototype activated this very eve. When your job is done, you may leave, and not a smidgen earlier." His cold, dark eyes never blinked, never faltered. "You know how to contact me when you're done, Mr. Hackerty, and I shall expect your call in due course."

![]()

As he headed home, Crowe's mind was free to wander, and he frequently took a longer route than was strictly necessary to encourage such pointless meanderings. He enjoyed the indulgence of the simple act of walking; the time spent gave his mind free reign to travel internally, to such places his imagination might lead it. He had done a great deal of his best thinking, plotting, and scheming, on his walks home from the office over the years.

As he clanked along the softly carpeted metal rails, each step held a memory, a part of the past that had led him to this day.

Two metres to his right was just such a spot, where he had stood ten years prior and sacked one Mr. Blenderbottom for the foolish act of gambling. Mr. Blenderbottom was no gambler by any means, and it would be unfairly unjust to imply that he was. It would be similarly unfitting to state outright that Mr. Crowe was by any means a proficient gambler, as his evening's losses, and Mr. Blenderbottom's subsequent firing, could attest to. Such is the lot of any such poor soul that catches the ire of an angry, and slightly less wealthy, Mr. Crowe, as he stumbles his way home, influenced to no small degree by a range of decreasingly fine vintage Romulan Ales, and a pocket full of losing betting stubs where a full purse had once resided. Mr. Blenderbottom had suffered the not insignificant misfortune of being that very unlucky person on just such an instance, and no amount of pleading, that without his beloved job, he would be forced to watch as his sick mother died a horribly twisted death, could possibly convince Mr. Crowe to change his mind. Happily for almost all involved, it was of little consequence, for the shock of his sudden dismissal was such that he surrendered his mortality that very eve with a strong line of hemp around his slender neck, and was forced to bear witness to no such event as his mother's further suffering.

Another step, and he took pause with a soft, misty eyed smile as he reminisced. This very square of smooth grey carpet reminded him of his good lady wife of some twenty eight years prior. He had been stood on that very spot when he first heard the news that her body had been discovered in a mysterious fire that had broken out earlier that day; and indeed, his presence on that very spot since the wee hours that same morning had been confirmed by a surprising number and diversity of compellingly credible witnesses.

But this was no time for nostalgia. His walk took him to where he could leave the station, a deck where a transport would carry him through the vacuum, safely from the station, to the outlying section where the habitats were situated.

This deck was higher up than his offices, and getting there required he step into a great glass elevator cabin, sailing smoothly through a tube that provided a view like no other, as they ascended aloft. The decking spread out before and below him, a vast scaffold of technology, a canvas upon which man had constructed a wondrous edifice to his spirit of adventure. This was a place in outer space, an artificial building, a city even, that was suspended against the elements, floating freely. It was a great metal tube, a shining silver and grey tower, with windows looking out into the endless night. Such a thing was truly an achievement beyond measure, that man had walked so far down the path of science in so short a time. Pure science, the fuel that drove the mighty engine of progress, was given form beneath his feet, but on this day such heady notions failed to rouse the very slightest measure of interest.

He looked away, lost in thoughts, and distracted unusually by his own internal ruminations.

"Computer," he said, to the gigantic technological mind of the station, which was always, always, listening. It responded with a pair of short toots. "Stop lift, I'll walk the rest of the way."

The doors slid open with a gentle hiss, and his feet tramped down onto a queer arrangement of metal flooring panels, that clattered very slightly with each footfall.

The walk before him was no short one, and yet he took it at a leisurely pace.

The shuttle-bus deck was filled with relatively small, metal, tube-shaped structures containing a number of seating apparatus. Each of the many tubes held a large number of people, waiting to be fired into the abyss, launched to the sprawling areas of the station that orbited the centre-piece, adrift in the mighty heavens. People, Humans, and their friends from the stars would be crammed in, sharing their journey, their wonder, and even their air, secure inside a man-made vehicle, a means of travelling in the most inhuman of climates.

All of that was well and good, but it was no place for a man such as Crowe. He had a shuttle of his very own, controlled by an artificial mind which could drive it with a degree of accuracy no creature, neither man nor beast, could aspire to. It was clean, with soft seats, and a fragrant air. Moreover, no Human, nor friend from the stars, would ever share his air, or befoul it with their common stench. He could travel in the luxury to which he had grown rightfully accustomed. He had no motivation to share his time, or his space, with those beneath his status, and his wealth meant he truly never had to.

His tired old body shambled along to the exclusive area, where his own transport could be found, but in his mind it made proud strokes, the strides of a much younger and healthier chap, filled with vitality now long since past. Why he had chosen to stroll on this day, he wasn't entirely sure, but he felt the need for a little time to clear his head before he went home, and a walk along the decking was as good a way as any, while his bones were still equal to the task, at least.

The windows along the wall offered a tantalising glimpse of the heavens, but he took no pleasure in such things this day. Tiny pinpricks of light, so far away that his Human brain could scarcely hope to fathom such distance, peppered the black canvas of the universe before him. He failed to muster any awe, any sense of majesty, from his distracted inner ramblings. Perhaps he had spent too long in this space; perhaps his sense of awe was as deadened as his humanity, and his compassion for his fellow man. Perhaps a life spent in the pursuit of his inner wants, had left him unable to take such simple joy as existed in the majesty of the world around him. Perhaps his lunch was merely disagreeing with him.

With a sombre, and unsatisfied mind, and a hopelessly withered heart, he traced his distraction back to his one-time friend; his mentor; his partner in business, and trusted ally.

He stopped a moment to stare through a window as, far in the distance, the section of the habitat complex floated lazily by, and he strained to make out the outline of his own luxurious lodgings.

Why he was so pre-occupied, he wasn't entirely sure, but lately, his years combined with his growing dissatisfaction had made his thoughts harder and harder to bring to heel.

Now he found himself drowning in ruminations of a man lost. He shook the thoughts away, and allowed himself a wry smile. "Silly old man!" he uttered, just loud enough to be heard, if anyone took the trouble to listen.

Time floated by even more lazily than the habitat complex. Suddenly, a sound drew his mind back to the here and now. A piercing, rude little whistle, which was followed by a voice from out of nowhere, carried on the technological winds. "Hackerty to Mr. Crowe." said the weedy voice, tumbling from thin air.

"Crowe here." he replied.

"Sir, it's ready. It's ready for activation at your convenience."

As the rude little whistle once more proclaimed that the communication was at an end, Crowe muttered to himself under his putrid breath. "Drat and blast that infernal Hackerty and his whimsical efficiency. I shall never get home at this rate."

![]()

Mr. Hackerty looked up to the wall. It was some time past eight O'clock, time long since he should be at home this Christmas Eve, to tuck his children into their beds, and tease them with thoughts of the morning, before they slept fitfully in anticipation.

Crowe glared at the device. A cylinder of metal, dull, and dark, with openings and adornments that served who could imagine what purpose.

"Sir." Hackerty gestured to the machine. "I think we should run another round of tests, Sir. It's complete, but I don't trust it; it gives me the heebie jeebies. It can wait a few days, can't it, Sir?"

"You're dismissed, Hackitt." said Crowe, his eyes never wandering from the serene little contraption. "Go home. Go to your family, that you miss so much." he added with clear disdain; a disdain that, far from making any effort to disguise, he deliberately forced into his voice.

Hackerty swallowed down thin air, and glanced from his employer to the device. "Surely you're not going to... turn it on, are you?"

"Hackerty, leave!" he said, firmly enough to leave no doubt that his presence was no more welcome, or needed, than that of a headache.

He needed no further telling, and he snatched up his replicated coat from the back of his chair.

Watching as his employee left, Crowe picked up the little thing. Barely a forearms length of metal, solid and weighty, and yet it held so much power. He stared at it, raptly, lost in the promises; lost in the dreams of him and his partner, himself now lost to the world so many years since.

It was time to live their dreams; it was time to bring their dreams into reality.

"This deserves a tipple, and I have just the bottle in my cellar." he postulated to himself with a tuneful hum. He took the dark little device, and he left for home, this time both directly and for good.

![]()

His home was a thing of modern wonder, and stood apart, even in this time of marvels. The doors were set to open for him alone, and they duly complied in their task as he approached, needing the assistance of no man to do so. Inside, partially hidden lamps flickered on by themselves, bathing the walls in a soft glow, with nary a candle nor lamp in sight of any eye. His lodgings were spacious by the standards of the time, and luxurious by any standards of imaginings. Long, white, and metal, panels stretched along the walls, punctuated by dark wooden affectations. It was all quite lovely, a sight to behold, and he had earned every inch of it, so he told himself. He had told himself so often, he had even come to believe it.

In fact, the lodging had not always been his own. It belonged to his company, as all things did in the long run, including himself, although he was loath to admit it.

This place in particular, was formerly the abode of his partner, Shrew. He was once a great man; a visionary in his own time; a legend, even in the small circles in which he rotated. He had built the company on his own strong back and keen wits, and grown it to a scale that demanded respect. Crowe had joined later, a mere child in comparison to the might of Mr. Prederick Shrew, the company founder.

Shrew knew how to do business in the ever shifting sands of the future. The industrial age had long since given way to the age of the technological. That, in turn, had passed to a time of pure invention; study for the sake of study; new ideas purely for the sake of advancement. Perhaps, business would have been a thing of the past, but men like Shrew understood the workings of society, even a society so advanced as theirs now seemed to be. He knew the minds of men, and how to appeal to their passing fancies; he knew to feed their wants, and flatter their egos. And just as there were great men such as he, there were men like Crowe, who knew how to exploit them and sail along in their wake.

In those terms, time may pass, but nothing of value would really change, and for them, at least, it hadn't. If he'd had a mind to realise such things, he would have noticed that he was a relic of a bygone age. The greed and ugliness of wealth, and the poverty it left in its wake, was gone, and should have been forgotten by then, for in the minds of the common man it most surely had. Men like Crowe kept such notions alive, living as they did, motivated only by self interest, in feathering their nests, and improving their status at the expense of others.

The house, if anyone would believe that such a mundane title could do it justice, floating among the stars as it was, was furnished with equipment to further the business of their work.

Crowe placed the device gingerly down on the desk in his study. He handled it like a man that could appreciate the true value of such a thing, but any value it might have to him was only in what it might bring him, not what it might do for anyone else. His equipment whirred and flashed to life of its own accord, as lamps bathed the sterile room in a blanket of white and blue making it appear alive and vibrant; like his home had a mind of its own, and a life beyond that.

"Computer," he demanded of the technological mind, residing in the furthest reaches of his home, "scan this item." And it complied duly, busying itself to follow his instructions as it was wont to do.

While the machine began its computations and enumerations, he slipped off his jacket, a beautiful thing indeed, and he rested it gently upon a clean surface, a white sheet of purest silk, but harder than the strongest of steels.

Suddenly, and without fore-warning, he appeared; and in that moment, everything changed.

Crowe stepped back agog as the apparition came forth. It was seamless and dark, austere, and as imposing as anything brought forth from any faction of reality.

He gasped, his chest heaved, his face sallowed, and he stared with eyes filled with the grimmest of terror.

"Shrew!" he rasped, and his friend, his mentor, looked back at him with a pair of bloodshot eyes.

"Crowe." it spoke, its voice low and deep, no different to the way it was when once his feet had walked the Earth. But it was not the same, for how could it be? His remains were on that very Earth, buried beneath a bush of roses, as per his request in life, for his wishes after death.

He was incinerated, burnt to powder, and placed in a park of remembrance. No man should come back from that, and what manner of man could?

"Shrew? How?" He scuttled back, his feet struggling to find purchase, his arm scrambling to his rear to find something to brace his weight. As fear bore down on him, mortal terror forced reason from his mind, and only the deepest of animal instincts remained. And the instinct told him to run, and run, and he wanted to do so, but his legs were as jelly, his chest was faltering, panic had him in its tender grip, and there was nowhere left to turn. He simply waited as the apparition made its way towards him.

It was Shrew, there could be doubt, and no doubt thusly did he harbour.

What was truly horrifying, truly the hardest fact to swallow, was that this was the man himself. This was no illusion, no shimmering light, no trick of the eye cast on smoke nor mirror. He was solid, as solid as you or I, and all the more terrible for it. Had he risen from the grave, pulled his disparate matter together, and ventured into the stars? To Crowe, it seemed that he had. What other explanation could there be?

Crowe could only shiver and shake, like a child waiting for punishment.

"You're... you're not here. You can't be here." he said, closing his eyes, like his not seeing it might make some kind of difference to the fabric of reality; might tip the balance of odds to his favour. "You're stress and strain, you're more proof of my over-working than ever a solid person was. You're no more real than a dream; a passing fancy. I have dined on Klingon cuisine, and passed gas more solid than you must surely be."

He opened his eye, just one, and just a crack. Nothing. He saw nothing before him. He huffed in relief, before hearing a familiar voice, off to his far left.

"I'm over here, Crowe." And just as he said, there he was, in all the solid reality there was for the universe to conjure. "Calm yourself, before you have an accident. I'm a hologram, and of no mind to clean you up."

A hologram, indeed, a fiction of light and power made matter, a technological marvel that threw an echo of reality so true, that you could stare upon it, and never know you were being fooled. This man was no man at all, he was science given form, and nothing more besides.

"You're... a hologram?" He stumbled over the words as his terror subsided, giving way to confusion, and no small measure of it. "How did you..."

"This is my lodging." it said, looking down on him with a certain lack of approval.

Crowe felt it, but had things on his mind that needed to be dealt with first, and ideally in short order. "By what means are you here?" he insisted, with a haughty tone of growing irritation.

"As I said, this is my lodging. I had the equipment fitted many years hitherto, that I might run... experiments, here in the evenings."

Crowe sneered at the very notion. Whether this was a man with a real heart beating in his chest, or a figment of technological imagination, there was a better reason for having such a wonder in his apartment. "Experiments, Shrew?" he sneered, with all good reason. "A man free from the burden of having a wife would surely find better reason to install such an appliance in his home, would he not?"

"What a man does in the privacy of his home, is his business, and his alone. And so, Crowe, I'm wondering what precisely you are doing in mine." The man of light and power sniffed, looking around, surveying the moderate changes that had been made since his time.

"You're dead." Crowe reminded him, dismissively, and in no uncertain terms, such an explanation being hard to refute, no matter what the means of his being were. "You're dead, and gone, and you're not coming back. I took over your apartment after the funeral. It was bigger and nicer than mine. I saw no good reason not to, and I see no good reason now."

Shrew, or the vision of him, at least, scowled, but had no argument to counter.

"Why are you here?" said Crowe, his fear once more put away in its proper place, and fast losing interest in the conversation.

"I, too, have been pondering this." it said with a look of deep suspicion. It slowly began to survey its surroundings, as if a good reason might present itself. And then, "Ah!" it emoted, with a dramatic widening of his eyes, its mouth a gasp, and an arm stretched sharply out to point directly at the cylinder of metal. "That!"

"That?" said Crowe, looking over to the device. "What's your interest in that old thing?"

It lowered its arm after a short pause, and returned its attention to Crowe. "I'm a hologram. I'm programmed to have an interest in... 'that old thing', as you so succinctly describe it. Why would I give a tinker's cuss about it, or you for that, elsewise? I have a function to fulfil, and thus I stand before you now, fulfilling it as we speak?"

"Well finish fulfilling it, and begone." demanded Crowe with weary disdain. "Unlike you, I have a life to lead; I have fine brandy to quaff in celebration, and a good full night of sleep ahead of me. Your best days are behind you; your worst days too, come to that." He gave a little snigger.

Shrew regarded him disarmingly, and Crowe shrunk slightly from his acid glare.

"Well you can stare all you like, Shrew; stamp your feet, and shout to the heavens, but it won't change the facts of the matter." he insisted, tiring of the encounter and long past trying to hide it. "And on the subject of 'matter', might I remind you, Shrew, that matter is the one thing you are not."

"No matter. I'm here to offer... a warning!" said Shrew somewhat chillingly, stepping up, and glaring down at the smaller man.

Crowe retreated in surprise. "A warning?"

"A warning! If I'm here, then that means... danger! Danger to life and limb, and danger most real!"

Crowe gulped and made no attempt to hide his trepidation, though any such attempt would be rather pointless in this case.

"That device." it continued, as it looked over to it, and once again raised its arm to point sharply at it. "That device... must never again be activated!"

Crowe scoffed. "My device, Shrew! My device." He laughed a grave little guffaw, and hardly the laugh of a man amused. "This, like your apartment, belongs to me. You died, and when you did, you left everything to your business. You left it to me. The device will be activated this very evening by my own hand, and tomorrow morning, I will be rich; rich beyond your pitiful dreams. And though you your existence now is little more than a pitiful dream, I assure you that I have dreams enough for the pair of us."

As he spoke, he had wandered over to an opening in the far wall; to a silver metal box with a row of lamps that glowed an unnatural blue. He entreated it deliver a fine malt liquor, and just such a thing materialised, as if from nowhere, shimmering into reality like countless glowing fireflies attracted to a flickering candle, which hardened into the very image of what he'd told it to become. He hoisted it out, and drank heartily.

"Drink, Shrew?" He offered, and then made another guttural croak, something akin to laughter, but holding not a shred of warmth. "Oh, I keep forgetting that you're dead. You seem to have forgotten yourself, but it's no hardship to me to keep reminding you of the fact."

"If you activate that device, Crowe, it is I that will be reminding you!" it said, its voice bearing every overtone of seriousness. "You will die, Crowe, and I shall remind you of this warning in the hereafter, as occasion should allow, or amusement seeks to satisfy."

"Really?" said Crowe with an ugly little smirk. "And might I ask you how you know this? How can you report this sorry fact from beyond the grave? If you were truly a spectral being, a manifestation of the worlds beyond our world, I might feel your words carry the slightest weight. But you are an illusion. You are the result of measurements, and scans, and light dancing to the command of its master. You are a shadow, and mine is the eye it is cast upon. You are an 'it', and hold no bearing to me."

The shadow bore down once more, but Crowe was unmoved. "Mr. Shrew made me before he activated the device himself. He spoke to me; he told me what I was to do, in the event of his passing."

"To harass me in life, it seems?"

"To warn you, lest your sanity abandon you, such as it has! Shrew conferred upon me this task. He knew that the device was dangerous, and told me that if it took his life, I would stand as a warning that nobody else should follow his path, and that wiser minds than ours be bid prevail."

Crowe stared into its steadfast eyes. He couldn't shake the impression, try as he might, that this thing was real, and really was his old friend. The resemblance was uncanny, striking, and completely undeniable. It was as if looking into the past, if the past were alive all around him. "You've warned me now, Shrew, so begone."

"Mr. Shrew, knew of the risks." it continued, paying Mr. Crowe's dismissal no mind. "This thing—this alien device—is dangerous. You must know this."

He nodded in agreement. Of course he knew; how could he not. The greatest advantage came from engaging in the greatest risk.

"When I—Mr. Shrew—purchased that device, for no small sum, we knew so little about it." began the visage, steepling its fingers and closing its eyes as if remembering for itself. "We ran every test; we examined every inch of it. We began to understand it; or at least, we thought we did."

"It's as dangerous as you make it." Crowe stood his ground. "It's alien, certainly, but it's an engine, a gadget, and nothing more. It manipulates time; it changes reality, and lets us travel faster than ever before. Once we harness the power of that thing, interstellar travel will change, and we'll be at the very forefront of the industry. I think that's worth a risk or two. You thought so too, Shrew. You were content to risk life and limb, back when you had either one to gamble."

"Oh yes, I understood the risks, and I knew them when I built this hologram. I built it to survive me, Crowe. I built it that it might exist after my demise, if the device did confirm my fears, and indeed caused such a demise." The image of Shrew huffed an imagined breath, and sighed. "My fears were realised, it seems, for another journal in my diary was never made."

"Since then, we have studied the device further. We understand it better." countered Crowe.

"And that is the very hubris that ensured my departure from this mortal realm. Crowe, Crowe, we should never have purchased this. It should have gone to the authorities for proper research, not to us, we pedlars of mechanical men. Our work is not with engines. I ask myself, what lunacy had taken me, that allowed this evil to find purchase in the fertile ground of my ambition?"

"Pedlars of mechanical men, we may be, but I aspire to become something more, as you yourself once did. The market for artificial life is saturated; it's done. We were too damned good at our role, in that sense. We need an innovation, and this new drive technology is it."

"Ignore me if you wish." said the hologram, in the most doleful fashion. "But it will be your undoing. I cannot prevent you from making the same mistakes as I myself have."

"Then we are finished." Crowe sipped at the remains of his drink. Good though it was, a bottle of something infinitely finer waited in his study. He tired of this game.

"And you will pay no heed to my warnings? You will suspend all reason and activate it?"

Crowe nodded that, indeed, that was his intent.

"Then I will tell you what is to come." it said with a sigh, and a shake of its head. "The present, the future, and the past, they will melt into one, and you yourself will be part of them none. They, instead, will be visited upon you, the spectres of the three levels of time: the past, the present, and the future. If, as you claim, you have understood its workings, then they will guide you to the destination you seek. If you are the simpleton I know you to be, they will only guide you to your death; or worse. There will be no escape for you."

"From the past, present, and future, and the hideous jaws of death itself, there is no escape for any man." Crowe smugly allowed an expression of victory. "Now begone with you. I have work to do."

The hologram, the dancing photon energy that formed the memory of a man, and the final echo of "danger" vanished, and plunged the room into an uncomfortable silence.

"Computer." demanded Crowe. "Activate my device."

![]()

He awoke with a start, his head sore from resting on the hard flat surface of a desk, the impression of a writing utensil left painfully upon his cheek. The room around him was dark, and truth be told, he couldn't be exactly sure what room it was; suffice it to say that it was not his cozy bedroom, and he was not tucked into his comfortable bed. It didn't even appear to be his own spacious home. Gathering his thoughts, he remembered the most troubling of dreams that had beset him previously.

"A hologram, Shrew?!" he muttered to himself as the fog cleared from his thoughts.

No; it was no dream, of that he could be quite sure. But could such a thing truly come to pass?

He remembered clearly; he had activated the device, and nothing. The world came to no end; the future crashed into the past only in the words of his old friend. Nothing of consequence had befallen him or the world at large. For a moment, a smile flashed across his wicked old lips, but then a thought began to trouble him.

Nothing of consequence had occurred on him, that much was true. The sky wasn't painted with fire, and his body remained... something of a disappointment to him, if the truth be told.

But his sense of self-satisfaction was somehow cut short, by a troubling notion he couldn't quite put aside. Nothing of consequence had occurred, that much was quite beyond question, but by that same vein, nothing of in-consequence had come to pass either.

His face took on a stony frown, as he came to realise with troubling certainty, that he had never gone to bed that night. He hadn't left the house in the dead of night. He had never even left his own lab, as he recalled. In fact, he had done nothing, except utter the words, "Computer. Activate the device."

What had happened next was simply that he had awoken with a start, in a strange place he was yet to identify. For a second time, he began to question if this was a dream. Was he, in fact, still dreaming, perhaps?

In due course, the darkness melted away, and he found himself alone, there inside a white laboratory. It was a thing from another time, a time in his past; his yesterday coming to life in worrying solidity before his very eyes. Yes... it was the lab aboard the station, a work-room where things had changed from dreams, and ideas, into solid reality, driven by the will of the men who worked there, under the relentless guidance of one Mr. Shrew.

He brought himself to his feet, and stepped gingerly around, faltering slightly with each wobbly, nervous footfall. There remained a gulf in his mind, an aching chasm between the fact that he was in the place from before this moment, and the fact of how the world had operated to his knowledge up to this point. He stared in wonder at each minute detail, each little thing reminding him of a forgotten tale from his past; there could be no doubt as to where he was. But how could this be; such things were beyond the means of man, even once the sheer might of science was tamed like the most stubborn of mares. The more troubling question remained not where, or even when, he was, but how it was that this could be possible by any means in nature.

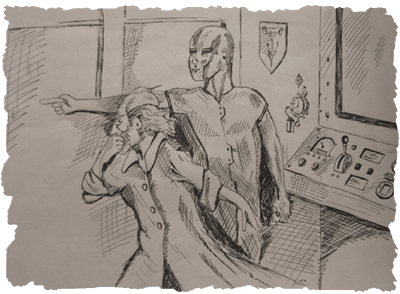

And then, there before him, he saw the figure of the first android prototype his company had produced.

It stood there serene and in austere silence. The face was white, too white to be flesh on those bones, to be sure. The eyes stared lifelessly forwards, and were clear black circles within balls of white. There was no breath, no movement of the chest. It was a dead thing, and it cast a shiver up his very spine just to look upon it. The first mechanical man. Not the first ever, to be fully correct, as there had been others. But this was immeasurably better by all means, truly the first of a kind. This had been built as a servant, nothing more; it had no aspirations, no imaginations of being something it wasn't. This was the slave that Shrew's understanding of humanity had dreamed of. It would never complain, never refuse, and never stop. It was built to obey, and wanted nothing more nor less.

He wondered what its true purpose might be here at this time; what it was sent to do, either for him, or to him. Nothing about this was making the first lick of sense.

Crowe suddenly jolted as the thing turned to face him. He clutched his hand to his heaving chest, rasping suddenly for his breath. "What..." he began to cry out, but the machine, the automaton, held up a hand; a gesture for silence.

"I am the past." it said in an eery monotone, bereft of any warmth of human speech. It was unquestionably just a thing. This was as dead as a statue, and though it moved, it was no more real.

"You're the past?" said Crowe, regaining some vestige of dignity, and clawing at his night-shirt to cover himself a little better.

"I am the past." it uttered in agreement. The second time of saying it sounding precisely, and decidedly identical, to the first. It gestured with an outstretched hand, and turned its head in a very deliberate manner to look directly at him, its glassy unblinking eyes staring forwards like two pools of oil, and with exactly no more passion.

Crowe began to move, and it took up position. It had gestured to the doorway through which his old office had once been and was again, against all reason he could find. His old office, indeed. When he first started with the company, he had been so raw, such a silly young fool. He smiled at the memory, now fresh from the solid reminder of his surroundings, so very undreamlike they seemed to him now.

Beyond the door, Shrew was stood, his arms crossed over his chest, as he peered out over the office. The company was larger then, but not by much. He had five employees, a mix of both genders: three engineers, a person who spoke, and a person who thought. It was all he needed for now, as the technology did most of the work for them, and Shrew stood above it all, like a vulture or a tumour, sucking all the life from a body.

"Crowe!" Mr. Shrew called out angrily. He remember that Shrew did everything

angrily, as his frown was permanently etched into his face, like it had been

carved from solid granite.

"Crowe!" Mr. Shrew called out angrily. He remember that Shrew did everything

angrily, as his frown was permanently etched into his face, like it had been

carved from solid granite.

Before he could instinctively respond, he heard a familiar voice call out from an unseen quarter, "Sir?" He then watched in silent bemusement as his own younger head popped up from behind his desk.

"In my office, now."

"But?" the older Crowe stammered quietly to the android, hopping from foot to foot and glancing around from face to face as the coldness of reality returned to his mind. "They'll see us, will they not? We should hide from their eyes, lest they catch us breaking the laws of nature, and panic grips them uncontrollably."

"They will not see." the android told him, its voice as stones dragged across steel.

"Not see us?" said Crowe, and he glanced again at the faces of the workers. True enough, if there was anything of them there to be seen, then seen they would surely already have been. Crowe calmed a little, and regained his balance by returning both feet simultaneously to the ground.

The android returned its stare to Shrew's office.

"I remember this." said Crowe, with a hint of an inward smile, as he watched the familiar sight of his younger self scuttle by. He turned to 'past', who remained impassive, removed from the events as if he wasn't there at all. "Do you have a name?"

"I am the past." it replied.

Crowe sniffed at it, and followed himself into the office. He settled against the wall, and was struck by the strangeness of how an illusion in his mind felt solid behind his back.

Shrew's office was a severe thing indeed. Pictures languished behind his desk of the man greeting, and shaking hands, with various legendary figures. The desk he sat at was a huge thing, carved from wood, polished to a bright sheen, and seemed designed to not quite fit in, so that it remained a striking contrast, and all the more noticeable besides. Shrew, himself, existed on the same principal. While the people of the time had evolved their social order to eliminate war, poverty, and greed, he had done no such thing. He remained separate from all that. He remained different, and he remained oddly proud of it.

"Sit down, Crowe."

He did, and nervously besides. The look on his younger face was approaching terror by now. The older Crowe could only smirk at the power he wielded. He had a lot to learn back then, and he had the very best of teachers.

"What is this is about, do you suppose, Crowe?" he said. He sat back and waited; the web was primed, and the spider needed only to wait. Either the fly was experiencing a lucky day, or else he had a little sense about him.

"I don't know, Sir. I really can't imagine."

The older Crowe smirked to himself, and turned to the machine. "I knew exactly why, of course." But the machine ignored him. Perhaps conversation was a thing he had no talent for.

"No, I don't suppose you can. I've heard that Miss Scruntywort has made something of a blunder." he told him, his fingers knotting before his face as he leant forward, causing the maximum amount of intimidation. It was working quite admirably too, as his two forefingers began tapping together just below eye level.

"She has indeed?" The younger Crowe feigned ignorance, and did an astonishingly bad job of it.

"She's made the kind of blunder that has cost me two things." He paused for moment, and then leant back in his chair, rolling his eyes to the ceiling thoughtfully, glorying in his own self-importance. "She's cost me money, and in no small quantity I'll add. And I know this means little to you, sitting there in your replicated shirt and trousers, but money means wealth, and wealth means luxury and power, something I value very greatly. By not crossing the T's, and dotting the I's, that silly woman has cost me money, and left me wide open to abuse." He turned to face the slightly frightened young man. "Of course, by me, I mean her, you understand?"

He nodded that indeed he did.

"And she's cost me respect. Hers, of course, is gone, and won't be coming back; but my reputation is worth something, and this kind of oversight lowers that value, which is something I cannot allow."

"Sir." He nodded in agreement.

"Miss Scruntywort shouldn't have ordered supplies from the Grumblegims. It was a foolhardy choice, as they are a silly people; their quality control is to no end frivolous at best; their workplace atmosphere is made toxic by the sound of singing, no less. The company, Dombey and Sons of the Bollobogs, they were the preferred choice; for they are a grave people, with calibrated expectations, robust innovation, and a deeply rooted commitment to ushering in a new paradigm in customer satisfaction. They also see to it that I get a hefty discount, and a bottle of something nice for Christmas. A woman in her position should have known better, but evidently, she didn't. What do you think of that, Crowe?"

"Foolhardy, Sir." The man flicked a wicked, avaricious little smile.

"Of course, if she was acting under the advice of others, one might interpret the situation with a slightly different slant, wouldn't you suppose?"

The younger Crowe's face dropped, the colour swept away in an instant. He knew; he had to know. The older Mr. Crowe simply watched, taking it all in.

"You, Mr. Crowe, advised her, and she acted upon your recommendations, without confirming the order herself. What do you have to say for yourself? Speak up, man!" The big man's eyes peered into his very soul for a moment, and the young man shifted restlessly under the weight of it.

"Sir, I..."

"Crowe!" he said, cutting him off; whatever there was to be said, was of little interest at this point. "You are an ambitious, awful, person, who's willing to damage the career and reputation of another, just to progress your own agenda. Am I wrong about you?"

"No, Sir." he said with a note of shame; a great deal more shame than he actually felt, or was capable of experiencing, in fact.

"I suspected as much. Let me explain something to you, Mr. Crowe." The big man settled, once again, into his chair. "I sell androids. My androids are by far the best there are. They do as they're told to do, when they're told to do it. Men seek such qualities, but they're not built into the women they most often pursue, and so it falls to me to build them on their behalf; and this has made me a very wealthy man. I'm sure you're following me so far."

Crowe nodded meekly.

"My wealth has afforded me, shall we say, an ability. I have the ability to have whatever I want, and it's with a certain sadness that I must report, that what I truly desire is to become a great deal more wealthy than I currently am. I want to become not just wealthy, but powerful too. I want to hold sway over the lives of others; I want to have power over the decisions of politicians, and great leaders of men." He paused thoughtfully for a moment, lost, no doubt, in the imaginings of his life as such described.

"With this in mind, I'm ready to begin working on the next generation of androids. Thinking machines, Crowe. Machines capable of talking, reasoning, the way we do. Can a selfish little prig like you even imagine what this will mean for us?"

Crowe shrugged somewhat weakly. "I believe I could only imagine, Sir."

"Let me tell you. We wouldn't be able to make them fast enough. They'd be grabbing them off the production line. Demand would outweigh supply to such a degree, we could name the price the sky, and they'd be cueing up to pay us double. They're not even that much different from the rubbish we're currently pedalling. A few tweaks in production that will cost us next to nothing. Of course, there are designs to be drawn up and worked over..." He could clearly tell the younger man understood, and didn't labour the point.

"Mechanical men, is a field I have sewn up for many years to come. So now, I'm looking for a fresh challenge; something quite strikingly different. And I believe I've found it, Crowe. I found... the device."

This was all rather an odd a thing to be telling someone convinced he was about to be sacked on the spot. Crowe seemed unsure where this was heading, but his older self, watching from the shadows as an observer from his own future, knew all too well, of course.

"The device is an alien contraption, a creation from another race, dwelling in the stars alongside us, and I acquired it for rather a heavy price. It's a contrivance for manipulating time and energy. I don't know how it works, exactly, but I will, you can be absolutely certain of that fact. It folds time up like a tablecloth after a picnic, so you can pass directly from where you were, to where you'll be. With the annoying difficulty of the present can effectively be removed, then in essence there's no journey to undertake."

His nostrils flared with pride, and he beamed an oddly ferocious smile.

"Imagine it! Instantaneous transport from one place to another. One second you were there in the past, and snap," he snapped his finger for effect, "you're right where you wanted to be, in your own personal future, and the journey you take in the present never happened and never will.

"The universal will change." His lofty eyebrows lowered over his steely grey eyes. "And I'm the one to change it."

"Yes, sir." said the younger Crowe, still not quite following.

"But my question is, whether you are the man to change it with me?"

"Me sir?" he asked, the most obvious of questions; perhaps the only question that could be asked under the circumstances.

"My vision goes beyond Miss Scruntywort and her silly idiocies. It's regrettable that she misplaced her trust, and made an error of this magnitude, but the fact remains that she did. I gather she's soon to marry some poor soul, so the small issue of her future here will take care of itself soon enough; and not a day too soon, if it means she can finally be shot of that ludicrous name.

"People like her are of no use to me now, but a man like you just might be, if you understand my gist."

The younger Mr. Crowe stared back with hungry eyes. "Yes, Sir. I believe I understand perfectly."

"But can you be equal to it? Can a vile little creature such as yourself have anything to offer me? Do you have the drive and ambition to climb your ladder to the stars, or are you doomed to just be a vindictive little opportunist in a worthless suit for all your days?"

"Sir, I have the ambition to be more than equal. I mean to sit as the head of this company one day, and I will, one day, engage this device and see where it takes me. Sir, I will reside in an apartment that rivals yours; I will oversee innovations that will boggle the minds of men, such as ourselves; I will take my role in heralding a new era of technical understanding; and I will own myself a piece of this galaxy."

"Perhaps. Over my dead body, Mr. Crowe." He nodded in approval, or perhaps out of agreement with himself. Who could truly want to know the mind of such a man. "You'll have every chance to do exactly that, if you've got the will to be a match to your words."

"And I did, you know." said the older Crowe, turning to the android. "I followed him until he began slowing down. Then, I learned how to take his lead. I own this company now; I made my mark with the next generation of mechanical men, thinking machines. I did everything that he only dreamed of doing."

"Program complete."

![]()

Once again he awoke, Mr. Crowe, and wake he did with a start; and more than a little unsettled. For a few long moments, he couldn't be sure if he was awaking from a dream, or starting a new dream afresh, but his mind and wits soon returned, as if from a long and comfortable sleep. This was his own bed, to be sure, and in his own home no less; of this much he could be certain. All the ornaments and decorations were in order, just as he'd left them, and not a thing stood out as being out of place, or in any way out of the ordinary by any means. Had it all been a dream then after all?

As gingerly as any man could, he rose from the bed, and it was then that he noticed a tremor in his hand, and sweat beading at his brow. Something wasn't right, and the nature of that something for now remained a puzzle. And this fact made him all the more nervous besides.

He shuffled nervously to the door. For at one time, that was all it had been— a door, two unusually strong panels which slid apart by some unseen method; but now, they took on a more sinister facade. What lay beyond them? What horrors, or pleasures, might exist behind them now? What secrets would be revealed, if the door were to be opened?

He shuffled, slowly, for some questions were best left unanswered; this he knew, without the shadow of a doubt. But all questions were eventually answered, and he feared that the answers he sought were horribly, uncomfortably, close.

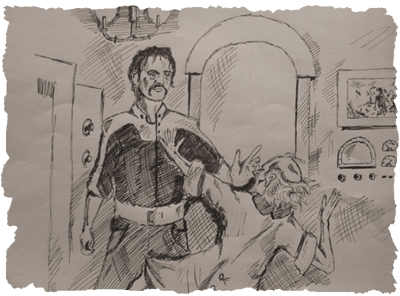

As he took one more step towards them, and sensing his presence, the doors duly slid open for him with a hiss and a whine. Beyond his room was a brilliant light, and beyond that stood the outline of a man. His silhouette was painted far more indelibly on his mind than on the wall outside, but, to be sure, it was indelible enough. There could be no question; there was an unknown man standing in his room. No more than he remembered going to bed, did he remember inviting any such man, into his home.

"Who are you?" he ventured fearfully. "I'm armed."

As the words slipped from his lips, he wondered why, and what part of him, could have chosen them. He was no more armed than he was capable of operating any weapon he might have had access to. He felt slightly ridiculous; a pompous old fool in his night clothes, posturing to a man, while in dreadful fear for his life.

"I'm the present." And with those words, the outline stepped forward into the bedroom, melting from the light, and into the darkness, his shadow fading in response as he became gently illuminated. "Obviously!"

An average man, he was, with a slightly empty expression; fatigued, perhaps, like he no longer had a care in the world, and no care even to find a care to care about. He was not a handsome man, yet not an unpleasant one either. He was a man difficult to describe, if you wanted a description of any more interest, than merely saying that he was strikingly average. He was average, indeed, bitingly so; shockingly, painfully, compellingly, and brutally average. From his nose, to the pallor of his cheeks, there was nothing too remarkable about him as to even cause one to notice.

Nothing, other than that he had upon his lip, a most meticulously styled and exquisite moustache.

His clothes were of a different kind altogether. They were tight-fitting,

black and yellow overalls. They had thin liners running along the length of the

arms and legs, and beyond the lowest extremities hung a pair of bare feet,

walking defiantly on Crowe's fine carpet. To finish off, he was carrying what

could only be described as a long coat, which seemed like it could never fit

with any other part of the rest of the picture. In fact, nothing was quite

fitting at all about the entire affair.

His clothes were of a different kind altogether. They were tight-fitting,

black and yellow overalls. They had thin liners running along the length of the

arms and legs, and beyond the lowest extremities hung a pair of bare feet,

walking defiantly on Crowe's fine carpet. To finish off, he was carrying what

could only be described as a long coat, which seemed like it could never fit

with any other part of the rest of the picture. In fact, nothing was quite

fitting at all about the entire affair.

"You're... an android, a machine, a mechanical man? You're a combination of engineering and science, made to take the form of an actual person, are you not?" Crowe's words were slow and deliberate, tinged with fear, and peppered with Curiosity. "You're wearing test equipment clothing, so you must be a prototype android. One of ours, I think?"

It stared back at him; the eyelids flickered slightly, and it's lips parted to speak.

"Well isn't that a perfectly pleasant way to greet a stranger, at this most strange of hours. An android... a mechanical man indeed? Why not just call me an artificial entity? A positronic presence? An AI on legs?! I've been called worse, sir, and with far fouler intent, by better than the likes of you, such that you are. Or aren't."

"What automated gibberish is this? Explain yourself! You say you're the present; is that how I'm to address you?"

The mechanical man shook its head in dismay, rolling its eyes upwards as it sighed, in as realistic a fashion as it was possible to imagine. Had it not been dressed in the garb of a machine from Crowe's own factory, there would be really no means to tell.

"Only Belgian progressive rock bands and flash-in-the-pan rappers call themselves 'The Present', Mr Crowe!" it said with haste and disdain, as it stepped forward and looked him over. "It... it baffles me sometimes, that your species even managed to... to find the ground to climb down to, after... after clearly doing so well for yourselves up in those trees, with... with... with all the nutrition rich invertebrates you could pluck from each other's fur casings!"

"Your words are strange to me, machine man." he said to the man-like machine. It spoke so oddly, being, as it was a thing from a world so different from anything that could now be readily understood. Yet, at least this one was capable of articulation. Now he may get some answers; some explanation of this most unusual turn of events.

"'The Present', in this instance, is a figure of speech, something I had been assured, wrongly it appears, that you would understand without further explanation on my part. My name is Mr. Wellington, and you may address me as such. And in anticipation of the sedate pace of your clockwork cog-mush, I will add that I am not the real Mr Wellington, and that you continue to remain outside the boundaries of what you would consider to be the normal flow of time. This encounter is not actually happening in any real sense, and nothing that transpires will be of any worldly consequence."

"No worldly consequence, you say?" A tiny flicker of a smile.

"Correct, sir. No consequence whatsoever. Nothing you do will affect my corporeal counterpart in any way."

"Your cor... But what of I? What consequence for me?"

"Who? Oh, yes... clockwork cog-mush... No doubt, you wish to be 'reassured', whatever that could possibly mean when your life amounts to... hurling yourself through savannahs, in a sack of swill and spanners, all boo hoo hoo, I'm being chased by a lion; boo hoo hoo, I'm being eaten alive! Then allow me to reassure you. Your situation is, shall we say, complicated. And not complicated in any sense that I would imagine a degree of solace may be taken from. You speak of consequence, but as you have failed, yet again, to grasp from my very first utterance, I am the present. There is no consequence here, save those of any such undertakings hitherto enacted, those you would call experience. Your experience—the past—brought you to now. Your actions now—the present—lead you to consequence—the future, where we are not. So on and so forth.

"The past... the future... neither are my domain, and I am not one for dabbling in conjecture, suffice it to say that everything you do or say is a matter of life or death, such as it is regardless. Take that as you will."

Crowe didn't like this, and was liking it less and less, the less he understood what in god's name was being spoken of.

"I really don't understand." he said gruffly, afraid, that perhaps he actually did. "Why am I here?"

"The device you so eagerly and ignorantly activated." said the android. "It is an instrument of technology that harnesses an immense power, ćons beyond your comprehension. It has fabricated these meta-environs to illustrate your circumstances in a manner befitting your intellect. Do you understand now why this makes me crotchety?! Do you think I enjoy thinking down to your level?!"

Crowe rubbed his temples. "But... this is confusing to me."

"I gathered that much." Mr. Wellington agreed, with a disapproving huff. "Talk to the human, they said. It will be easy, they said. They're slow, but they get there in the end, they said. But you don't usually get there, at all! You were given one clear instruction—do not activate the device! And what did you do?! I mean... was there some kind of... subversive ideological agenda at play, capable of distorting perception to such a bold degree that... that up becomes down, and black means white? And... I bet you never even considered my feelings, because now I'm the one tasked with trying to make you feel better about your act of... of... wanton stupidity."

Crowe listened intently, trying as he might to understand the increasingly bizarre words spoken.

"Look... Would it make more sense if I clobbered you on the nose with a rolled up newspaper? What it is you're not understanding really is quite beyond me, so let me spell it out in terms a dog would understand. When you—Crowe—activated the device, it—the aforementioned device—caused your time-stream to collapse. Present, past and future are diverging, and have pushed, are pushing, and will push, you—also Crowe—out of existence. Now, I'm no more a temporal engineer than you are a philanthropist, but as an android, and a janitor to boot, I favour my odds higher than most at cleaning up some of your mess, and though the odds remain microscopic that it'll make any discernible difference at all, you should not let this concern you—the real Mr Wellington will be fine either way; and that's all that matters.

"So with that, Mr Crowe, are you ready to see your present?"

Crowe sagged visibly, his shoulders round, and his head hanging between them. "I know my present, how could I not know?"

Mr. Wellington smirked at the very notion. "What could you possibly know about anything?! You, a network of vile chemicals and electrical pulses forced into activity by an easily damaged driver hub; a digital feed to a biological apparatus running on hard-wired instincts and irrational protocol functions. What could you possibly know, when your facts are malleable, indistinct from guesses, and your reality a shadow? You are a conceit, a fancy, a metaphor, nothing more."

Crowe grimaced and found his temper. "And then, Sir, what are you? An android, a machine? You're nothing more than a mechanical copy of a man, a thing that follows orders, a creature purchased and owned at the whim of a better creature."

Mr. Wellington shook his head. "Better creature... Now there's an oxymoron."

![]()

And with that, they were inside a house, a home, or some version thereof that existed on this station amidst the stars. One moment, it had been his bedroom, and in the blink of an eye and no longer, they were in a place altogether different. It wasn't his house; in fact, it resembled nothing he had seen before. It was dark and crude, a box, with a smattering of personal effects that slightly coloured the flavour of it; did some little thing to hide the sterility, to mask the artificiality of it all.

Crowe glared around. "What fresh hell is this? If, Sir, your job is to show me my present, then you've taken a left, when a right was in order."

Mr. Wellington snorted a huff of sound umbrage, and crossed his arms defiantly before his chest. "You are here now. This is your present." he said, rather flatly, and in a way that could leave him in no uncertainty.

"How could this be my present? Have I fallen on hard times: for these times seem hard enough for any man to bear."

"Strange though you may find it to conceive, a universe does exist outside your immediate perceptions, and doesn't disappear when you close your eyes. This is your present, but it is not your house. Geez louise!"

"Then whose?" Crowe, still rather daunted by the whole experience, heard voices from beyond a door. He pointed his finger towards it nervously, and looked towards the android. "And what will they say when they discover us?"

"Much like your earlier excursion, your presence here will go unobserved." it said with a tired huff. "As I've explained already, we are displaced from your reality; mere spectators. We can see them, but they can't see us."

"And what, exactly, are we here to spectate?" he said with ire, his bony old arms crossing over his chest now too, a gesture which was helping, somewhat, to close his night-clothes, and preserve a shred of modesty, yet barely a shred and barely modesty besides.